The Open Door

The Open Door

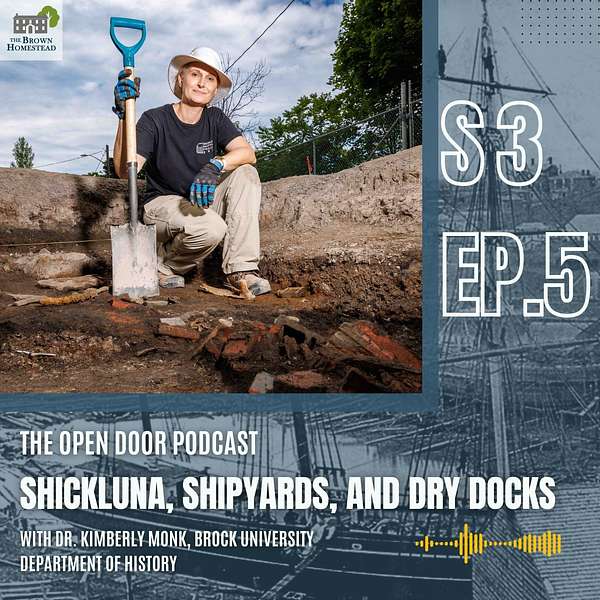

Shickluna, Shipyards, and Drydocks

Much of Niagara’s urban history is closely linked to our marine history, particularly after the Welland Canal began operation in 1829. Maritime archaeologist Dr. Kimberly Monk has worked to piece together the nuances of the local shipbuilding industry of the early nineteenth century, and, in this episode, delves into the major players, their contributions, and challenges in an era of changing technology.

[INTRODUCTION]

[0:00:08] ANNOUNCER: Ahoy. Welcome to a nautical episode of The Open Door, brought to you by The Brown Homestead in the heart of the beautiful Niagara Peninsula. Anchors aweigh!

[INTERVIEW]

[0:00:24] AH: In the unlikely event that you've taken a close look at the City of St. Catharine's Coat of Arms, you will have noticed the motto industry and liberality, and why not? It's the manufacturing centre of the Niagara region and has been for a long time, perhaps beginning with Duncan Murray building a mill along Twelve Mile Creek before his death in 1786. Where there's industry, there must also be transportation, which in those early days meant ships. The then village of St. Catharine's and the Twelve Mile Creek in particular became a hub for shipbuilding and supporting industries.

Now that, of course, is the very short version, and I'm happy to welcome Dr. Kimberly Monk here today to offer a little bit more detailed and a much more entertaining version of our local maritime history. Dr. Monk is an Adjunct Professor of History at Brock University and a Research Associate at the Niagara Community Observatory. In case you think intellectuals don't like to get their hands dirty, she's also a licensed archaeologist and has been leading the Shickluna Shipyard Project, a multidisciplinary investigation of the history of the Shickluna Shipyard here in St. Catharines. Welcome, Kimberly.

[0:01:30] KM: Thank you, Andrew. It's lovely to be here.

[0:01:33] AH: It's great to have you here, and I feel like this has been a long time coming, because it was some years ago, just when you were starting the project that we first spoke about this, but I know you've been doing a lot of work since, so maybe we can take advantage and learn about some of the things you've been researching in recent years.

[0:01:47] KM: Well, I'd love to. Absolutely.

[0:01:49] AH: Now, we're here to talk about Shickluna Shipyards and Dry Docks. But maybe we can start with a little bit of historical context and talk about what the St. Catharines of the early 19th century looked like as compared to today.

[0:02:02] KM: If we think about Niagara, certainly from the period of indigenous histories, we're looking at a wild landscape. We're looking at a landscape that was forested, where very early agricultural developments would occur. Certainly, one of the main aspects of that landscape would have been the waterways, the creeks, and the inlets that would have supported local fishing and certainly, trade.

We certainly can look at indigenous watercraft and consider that dugout canoes and birch canoes and later, small fishing and work boats that were built by the early settlers would have most likely been constructed and employed on Twelve Mile Creek for a variety of different purposes.

Certainly, St. Catharines evolved around its marine sections through its marine elements. When we think about the region, we really need to look and focus on how water was the route for which many of these industries would develop.

[0:03:10] AH: As you touched on that, even predate settlement, the inland water roots were very critical to the pre-settlement population, the indigenous population, and it only continued thereafter. As you're saying, there wasn't much St. Catharines there at the time. But as early as the 1780s, Robert Hamilton built a trading post, as we talked about right along the water there, where the Iroquois Trail, now St. Paul Street crossed the Twelve Mile Creek. While there wasn't much else there at that point, some have speculated that may have been the farthest point to which those really early boats, those small flat bottom boats were able to navigate.

[0:03:48] KM: When we start thinking about industrial developments, when we start thinking about how St. Catharines would eventually be a throughway for navigation, we have to go back to Hamilton's, of course, original route along what is now the Niagara Parkway and, of course, along the Niagara River. How, in fact, merchants such as Hamilton had put forth an act of 1799 toward actually a way both by road and waterway to connect, basically, Lake Ontario and Lake Erie trades. Unfortunately, of course, the War of 1812 occurred and that act was put aside.

Ultimately, when we start thinking about these origins, there had been certainly a long period whereby these waterways and these connections were understood to be integral to the development of the Niagara region. Ultimately, after the war, those efforts were certainly put into focus, of course, by none other than William Hamilton Merritt, and not necessarily because of navigation, but of course, because of water power. Again, it comes back to water being the focus. Water was not only something where you could float up, float boats on, but of course, it was necessary for the early industries to develop.

William had basically purchased a mill along Twelve Mile Creek, which then needed more water power and that would ultimately lead to his request to the government for a survey, that then led to, of course, further developments and the need, or rather the request to the assembly for the Welland Canal Company, or to establish rather the Welland Canal Company.

[0:05:40] AH: You make a good point there. When we talk about the industry, really the earliest industry was the mills. They were very practically necessary for the settlers to survive. William Hamilton Merritt was one of the early millers, and I mentioned Robert Hamilton opening his shop, but he had taken over Duncan Murray's mill upon Twelve Mile Creek near the escarpment. That draws to mind that we talked about how different St. Catharines was, but Twelve Mile Creek was very different at that time, too, before it was adapted for use as a canal. It was a very narrow [inaudible 0:06:12], unreliable water source, and millers like Merritt and Hamilton and John Decew up on top of Decew Falls there all found the water supply to be pretty unreliable.

[0:06:23] KM: Oh, if you look at certainly some of the early maps of the region, I mean, you can see the changes of Twelve Mile Creek, and of course, what would become Martindale Pond. I mean, they were significant, significant developments not only prior to of course, the first Welland Canal, but certainly after the first Welland Canal in the construction of the second Welland Canal. I mean, the wondrous maps that they hold, of course, at the Brock Map Library are just phenomenal, when you start to look at those changes and really think about human engineering that would allow for not only, of course, navigation, but of course, water power that would really push forth an industry that just was at that period in upper Canadian history was seen nowhere else industries that again, would evolve because of this wonderful development here in Niagara.

[0:07:19] AH: It was in service of that industry as you touched on that led to the building of the Welland Canal, which for those who aren't familiar, the first Welland Canal was begun around 1824, opened in November of 1829, which the building of the canals along meandering tail unto itself. But anyone who's read about the early history of the canals likely heard of a couple of somewhat famous ships now, the Ann and Jane and the R.H. Boughton, which were famously the first two ships to pass through the completed canal. But there were several other ships using the canal even before that, weren't there?

[0:07:54] KM: Well, there were. Certainly, the very first ship that was of course launched into the Welland Canal was the, actually, named Welland Canal by a man by the name of Russell Armington. The ship, of course, was built by, well, in conjunction with a man by the name of Job Northrop, who had quite an interesting history, but the two of them had produced the ship. Unfortunately, the size of the vessel was too large to fit through the actual locks of the first Welland Canal. That wasn't a great success.

But it was a very – it was actually a much more heralded event above and beyond what happened with the opening of the first Welland Canal. There was much fanfare around the launch of these ships. Of course, Russell Armington and the site where the Welland Canal was launched from, or the ship to Welland Canal was actually where the Shickluna Shipyard is today.

[0:08:50] AH: I love you talking about the celebration because I remember reading an interesting piece about that, about the cheers and toast and even celebratory musket fire when the Welland Canal, the ship Welland Canal made its first launch. It really speaks to that period in an interesting way.

[0:09:04] KM: I would also say that article by Alan Hughes, actually, which is actually housed on the Department of Geography at Brock University's website is fascinating in so many different ways. It really brings out not only what happened, but also who wasn't there. Of course, William Hamilton Merritt wasn't there. He was still pitching, of course, his plans with the overseas at that time. He wasn't actually there to see the fruits of his labor, which is unfortunate, of course, but again, it tells of a man who was determined to make this a success.

[0:09:38] KM: Yeah, definitely. If you're going to attach the word driven to somebody, it would be Merritt for sure. Russell Armington, as you mentioned, was one of the earliest shipbuilders building on what later became the Shickluna site, he built the Welland Canal and later more ships established, or tried to establish a permanent shipyard on that site. But unfortunately, his health didn't hold out. By the mid-1830s, he was not well and died in 1837.

[0:10:07] KM: There are a lot of interesting aspects of Russell Armington's legacy. One thing, of course, was that he was the one to initiate with the board of directors of the Welland Canal Company for the construction of a dry dock. He did that in March of 1830. One of the very earliest applications for a dry dock on the Great Lakes was by Russell Armington. It wasn't until later that actually the permission for dry dock would be actually allowed. Again, the Upper Canada Herald wrote in 1830, in December of 1830, that they were asking for proposals for the lease of a dry dock for repairing vessels.

Then later on, by 1831, they confirmed a lease, not specifically to Russell Armington, but to William Hamilton Merritt and John Donaldson. Of course, that lease, while they may have been the proprietors for that dry dock, it was Russell Armington, of course, who was the actual individual who was charged with clearly undertaking those repairs.

[0:11:12] AH: Now, to clarify for myself and for anyone who may not know, my understanding, you tell me if it's more nuanced than this, a shipyard is for building ships. A dry dock is for repairing ships. Is it that simple, or is there more to it?

[0:11:24] KM: Well, there is a little bit more to it. Of course, shipyards were known as boatyards. They were also known as dockyards. These terms were variously applied, depending on the size and the type of vessel that would be built at those locations. They were also, of course, locations for repair, even just a ship sort of just pulling alongside a dock within the shipyard facility could be repaired. Of course, the problem really came when those repairs had to be done below on the lower hull of the ship, below the water line. Of course, in those cases, then you need to build facilities in which to allow for the ease of repairing those sections of the vessels.

For example, marine railways, which were essentially an inclined plane, or track that extended from the shoreline into the water. Again, they required a cradle which allowed for the ship to first float onto that cradle. Then, of course, using a series of hoists, possibly blocks, and lines. Then, of course, powered by either horses or later by steam power. The ship was then pulled out of the water and onto a slip for cleaning and repair.

These were really what many of the certainly, smaller shipyards, medium-sized shipyards would have had early on. Marine railways allowed for, again, ships to be pulled out and repaired. They were a cheaper, much cheaper alternative, of course, to dry docks. We see marine railways and there are suggestions that there were a number of marine railways along, well, within Niagara by the 1820s. Possibly, Russell Armington had one. There was certainly a suggestion that there was a marine railway at Port Dalhousie under Robert Abbey by at least the 1840s, and in certainly a variety of other locations across the peninsula.

Then we come to the next level of technology, which were dry docks. Dry docks is basically, a general term for a variety of different structures. We won't go into all the different types of dry docks, but specific to St. Catharines, these would be termed as either graving docks or floating dry docks. Not to be confused with floating docks, which, of course, maintained water levels within a harbour area. Floating dry docks.

Now, floating dry docks were buoyant structures that, again, consisted of one or more sections. They would have initially been built of wood, later wrought iron was used, but they were built with a form, a U-shaped form with, of course, the lower portions consisting of one or more pontoons with mounted side walls. The sections were compartmentalized, so that they could be filled, or emptied with water in a controlled manner to sink or, of course, to raise the dry dock. We know, of course, of one floating dry dock on the Niagara Peninsula, and that was, of course, Alexander Muir, who operated his floating dry dock from around 1853.

[0:14:34] AH: They're a very interesting case, the Muir brothers and Alexander Muir. We'll talk with them. Going back quickly to Louis Shickluna, who took over our maintenance site, he had a dry dock as well. But he probably was the most, am I fair to say, the most prolific shipbuilder of the group of them along the canal?

[0:14:52] KM: Absolutely. Without question. Not only was Shickluna known for his skill, but the variety of different types of vessels that he produced, and, of course, the quantity of vessels that he produced was significant, not only in the Niagara region but across the Great Lakes. We have records of him building at least 100 ships across the Niagara Peninsula, and probably more. He also built a number of work vessels, scows, and other work boats for local port cities, but also for work on the Welland Canal. That was only part of his business.

While shipbuilding and building ships by spec and under contract was a big part of his business, it was only 50%. The other 50% came from his work on shipbuilding repairs and significant rebuilds at his dry dock.

[0:15:51] AH: We talked about now Shickluna and the new dry docks and so on, but they weren't the only ones either. You mentioned Robert Abbey earlier. He was another very early shipbuilder, I believe, from Scotland?

[0:16:01] KM: He was. That's right.

[0:16:03] AH: He established a shipyard at Port Dalhousie, yes?

[0:16:07] KM: At around, certainly the same time that Shickluna was setting up his facilities along Twelve Mile Creek, Robert Abbey established his boat-building business at Port Dalhousie. We’re not quite sure exactly where his shipyard was, if it was just inland, where of course, Martindale Pond is, or if it was actually on the shores. But unfortunately, no maps and there are no references specifically to the location.

We know he had a shipyard and we know also that at least at some point, he had a marine railway. I think we still need to debunk some of those histories to learn about the early Abbey facilities. It wasn't a massive operation, I would say. He did a lot of small boat building and boat building repair, or boat repair. He also, by the 1840s, started to build larger vessels, a Perseverance, and another vessel named The John Tibbetts, I believe, were both from his shipyard.

Understanding these shipbuilders, there was a lot to them and to their business to be successful, not only in shipbuilding, but of course, in ship design, to really design the first ships that would make this navigation possible, but not only possible, but actually, financially advantageous.

[0:17:26] AH: Speaking of Robert Abbey, clearly his was something of a family business. His sons working with him in Port Dalhousie. Two of them, John and James, moved to Port Robinson, where they opened up a shipyard themselves. One of the interesting stories I heard about their shipyard was that when the first Welland Canal was replaced with the second Welland Canal, they converted some of the early locks into a dry, or one of the early locks into a dry dock.

[0:17:51] KM: Correct. Yeah, they followed suit with Shickluna having done so actually with his dry dock. Transitioning an old lock into a dry dock was, well, smart business, because you didn't have to dig out a whole new area in order to install your dry dock space. Using, of course, the labours of someone who had, back in the 1820s, already dug that space, was a good way to get the job done quickly and without as much cost.

[0:18:21] AH: Presumably, there was some mechanism in place for removing and returning water, which is critical to a dry dock anyway, so it would seem like a smart choice. Yeah.

[0:18:29] KM: Yeah, they operate quite similarly.

[0:18:31] AH: From what I understand, the Abbey Brothers stayed in business until around 1874, which was a significant date in canal history, because that's when the third Welland Canal opened, which meant for the shipbuilders along the Twelve Mile Creek, a couple of things. Number one, the canal no longer passed through St. Catharines, but also with the larger locks, it sharply reduced the demand for the types of ships that people like the Abbeys and Shickluna were building.

[0:18:57] KM: Correct. Certainly, not only that, but I mean, the properties generally where these operations took place were taken back, basically, by the Welland Canal Company for its operations. It forced many of these shipbuilders out of business, including the Stevens Andrews, and ultimately, the Abbeys as well, was in operation certainly through the 1870s.

There was another request for another dry dock, and in fact, the next dry dock, which was in a slightly different location, would be then operated by the Andrews, by descendants of Steven, or rather one of his sons, William Andrews. We do see also some continuing advantages, the Welland Canal Company, realizing that they needed to continue to provide infrastructure for shipbuilders and ship repair.

[0:19:54] AH: There was a continuation, as you said, Steven Andrews, who was in business with Donaldson, who had opened that earlier dry dock, and later with, they were Donaldson, Andrews and Ross and subsequently, Andrews and Sons. Now, speaking of Steven Andrews, even though his, or his operation was one that was put out of business, there was a real continuity there largely through his sons, one of whom Stephen Decatur Andrews moved up to Collingwood, where he was very prolific. Another son, William, ran an important operation in Welland.

[0:20:24] KM: William, his eldest went on to operate the dry dock facilities of Welland. It became the Welland Dry Dock Company. Ultimately, SD, or Stephen Decatur, went on to operate the dry docks at Collingwood. We have a real family success story of three members of a single family going on to individually be enterprising in their own businesses across not only Niagara, but of course, up on Georgian Bay. As certainly trade and developments in the timber industry developed, we start to see a number of the members of these families move to Georgian Bay.

The Abbeys, for example, one of the members of their family went up to Owen Sound. See, the Simpsons as well, who went up and worked in Owen Sound. There's this change in the industry by the 1880s, and it's a movement away from Niagara and to a number of other areas within the lakes, meeting demands locally, but also as the trade changed.

[0:21:29] AH: Then there was Alexander Muir, who you mentioned earlier, and the Muir brothers across the creek from the Andrews operation. They were a success story in the fact that they lasted beyond 1874, one of the few that did. That was largely by focusing on repairs.

[0:21:46] KM: Certainly, the Muirs are noted for building at the very minimum about 20 holes. But the majority of their business was always about repair. I mean, it speaks volumes that Alexander Muir, even before he set up his shipyard was already thinking about a repair facility, a floating dry dock. Ultimately, with him and his brothers going into that business, having quite a number of hands in order to complete this work, they realized, of course, that operation for repair was a requirement, especially as many of these canals were getting on in years.

A year at sea would take its toll on any vessel. As, of course, the age of vessels would go on, and if vessels weren't lost as a result of accidents, and certainly, even if they were, some of them would be floated and brought into dry dock for significant repairs, and sometimes rebuilds. We start to see this increasing demand for the older vessels that were plying great lakes requiring these facilities and requiring them quite regularly as well. Operations such as the Muir's would have been significant in order to meet demand.

We're starting to see this demand increasing by the 1870s. I suppose, when we start to look at Muir's facilities, he was fortunate. He was on the west side of Martindale Pond. Of course, all of the developments that would happen with the opening of the Third Welland Canal would happen on the east side of Martindale Pond. Poor Donaldson and Andrews and Ross would have to move their facilities, so that it would make way for, of course, the new locks of the Third Welland Canal. That, ultimately, put them out of business, or at least at that particular location.

[0:23:34] AH: Now, I take it that the success that they had in continuing was because although different types of ships were being built for the new canal, the older ships remained in service. As they got older and they needed this extra repair work, people like Muir were able to capitalize on that.

[0:23:52] KM: Indeed. Certainly, there was also, for many of the vessels, depending on the type of vessel operating, and I do have to mention here, especially the book trade vessels, only because the nature of their trades, they often would carry two types of cargos over the course of a year. They would carry timber, or they would carry wheat. They would have to be rebuilt, or reconfigured during the middle of the season in order so that they could have accommodations ready for the types of cargos they were carrying.

We see these ships coming into dock in around July before the harvesting season and getting most of their cargo allocations changed. This is where again, having these repair facilities was critical, was to make sure that the owners were capitalizing on the markets and ultimately, those staple products that were being, well, sold at obviously higher rates depending on the season.

[0:24:51] AH: When we talk about supporting businesses, it's more than just repair. There are these things and many other aspects too, like sale making and what are some of the other support industries that grew up around it to support the transportation?

[0:25:05] KM: Well, of course, it was a homegrown industry. As much as you would have the shipbuilders to build the ships, you also, of course, needed a variety of different suppliers to fit out those ships. For example, we start to see the development of sails makers, or rather, the industry of sails makers within St. Catharines. For instance, the Robesons and the McCourts, which were located initially in St. Catharines, the Robesons moving to Port Dalhousie eventually by the 1870s. Again, these were families of sail makers that were producing the sails, that would, of course, be fitted to an individual ship.

They were also often riggers. They would be the ones to actually set those sales after the ship had been launched. I have a number of interesting records that I found at the St. Catharines Museum in fact, which talk about, which provide an account for rigging a vessel that was built at the Abbey Yard and rigged at Shickluna’s Yard in 1854. It's fascinating because it talks about all the different materials and the amount of sail that they would have required to fit out one of these ships.

We see an increasing amount of advertisements for these related industries along the cal. Certainly, sale makers was one such industry, but we also start to see other local businesses, those who provisioned the vessels with everything that they needed to set forth on their voyage, their grocery provisions for the vessels. We also, of course, one very important industry as steam power, of course, was developing was the machinery, of course, for paddle steamers and the canal propellers that required specialized boilers and steam engines and other interior machinery.

Men such as George Oill, who operated a foundry at Lock 4, was a key support for Shickluna, for building and launching a number of his ships. We see him moving to St. Catharines in about 1847 and operating certainly through the 1870s. There was a great demand for the business, but there was also a lot of competition for these businesses. They had to be astute businessmen in how they flogged their wares, so to speak, and ultimately, to make sure that they remained competitive in pricing because there were others that even Shickluna went to over this period.

[0:27:35] AH: A lot of support businesses meant a lot of mouths to be filled.

[0:27:38] KM: They did, indeed.

[0:27:40] AH: Speaking of mouths to be filled, a very important part, especially the early canal, was a need for horses.

[0:27:46] KM: Oh, absolutely. Of course, those poor beasts, the burden would certainly tire out and they would often have set at either end of the canal, stables and barns for ships to be replaced at the beginning, or end of a voyage, so that they would have, of course, sufficient horsepower to pull the ships along the canal from, of course, Port Dalhousie to Port Colborne.

[0:28:11] AH: Which is why we now have in Port Dalhousie, had long last a monument to those hard-working tow-hosts, horses, and I get to drive by it most of the days. I love seeing the monument there. Anyone who hasn't seen it, I encourage you to go take a look at it. It's an overdue recognition for one of our important partners in the early canals.

Now we've talked about a lot of these big names, and we've focused a lot on Shickluna. He was the most prolific. But you have, obviously a special relationship with Louis Shickluna through the Shickluna Shipyard Project, which, if I'm correct, has been going on for four years now?

[0:28:46] KM: Well, we received the grant in 2018 to undertake excavations of the shipyard. Of course, my relationship with Shickluna and his history began many, many years before that in about 1997, when I began the Underwater Archaeological Survey of the Sligo at Toronto, just off Humber Bay, and where we undertook an archaeological survey of the site and created this photo mosaic, one of the very first that was actually produced long before we had all this fancy software. We literally had a team piecing together the individual photographs that amounted to this wonderful photo montage of this underwater site.

That particular ship, the Sligo, was launched by Shickluna at the shipyards in 1860, and known as the Prince of Wales originally, and she served the high-volume, low-value book markets across the Great Lakes from between 1860 and through until 1918, when she was lost at Humber Bay. I had a very long-standing relationship with not only, of course, studying this vessel, but studying the ships that were built to fit through the confines of the Welland Canal locks, known as Welland Sailing and Propeller Canalers.

That, my study of these ships. Then now, of course, the study of the shipyard go hand-in-hand, to better understand, of course, this connection between those who crafted ship timbers and produced something that would advance economic development would not only advance the local economy, but our national, and even the international economy, because clearly, we are a bi-national canal. The benefits to sharing, of course, the wealth of that artery with our American compatriots.

[0:30:37] AH: That's an interesting context because you had that background when, before you even began the excavation at the Shickluna shipyard. I'm curious, in terms of the process there, what have you discovered that has changed, or added to your earlier understanding of Shickluna and that arrow shipyard?

[0:30:55] KM: I feel that our work at the shipyard has enabled a much broader sense of shipyard operations, in understanding how the site was organized, in looking at the wide variety of materials that we have at our disposal to understand how the site changed over time, how it was shaped to meet the needs of his business. But also, to speak to the man, to speak to his diversification, to speak to his business acumen, to also better understand the nature of labour and the variety of challenges that no doubt were felt not only by Shickluna but by the other shipbuilders. Certainly, labour strikes was a big issue. There was as part of a talk that I gave to the St. Catharines Museum, Adrian Petrie had spoken about, of course, the labour strikes. It was an important moment for the shipbuilders because, of course, you have all of your labour striking and you've got deadlines to meet with your shipbuilding contracts.

How would you get more men to help build ships? There was constantly a lack of supply of manpower in order to build ships. This is from as early as Russell Armington, you can see him begging for people to come and move to St. Catharines to help him build ships. The perhaps lack of skills in the ship trades was a problem throughout this period. Understanding what Shickluna had to contend with, I think, is one of the certainly lessons of reading the shipyard, of looking at how he built that basin, how he dug out that basin to, of course, the types of buildings and how they were repurposed over time to fit demand and need at the shipyard, and even by later occupation of the site.

We're still trying to get to the root of some of the aspects of his shipyard buildings, of course, through our excavation work, and we're really looking forward to the work that we will be doing also at the Shickluna Dry Dock, his double dry dock, again, which was initially commissioned by the Welland Canal Company in 1846. Shickluna won the contract to dig out that dock, that dry dock. In fact, it was dug out, of course, by Lock 4 on the first Welland Canal.

Again, he didn't have the full work, just like the Abbeys ahead of him. He had some help along the way, but eventually, he would own that dry dock and ultimately, extend its capacity, so he could fit two ships in. He's thinking ahead. He knows that the demand will actually repay and reward his industry. We're looking forward to examining that site as well in conjunction with the shipyard, because it really speaks to the whole shipbuilding complex, to how, again, this shipyard really became not only the biggest and most productive on the Canadian Great Lakes but there's definitely some rivalry for potentially being the most active shipyard, at least in the 19th century across the Great Lakes region.

[0:34:08] AH: That's the exciting part of it, is that it's still as much work has been done as an ongoing project, there’s more to learn and more to discover. I know that's something that's been captivating to people here in St. Catharines. I should commend you at this point because you've been very generous in terms of using this project as an opportunity for people. I know people who have volunteered and been able to participate in the dig there at the shipyard, which is fantastic. Also, we've used this as the basis for classes that you've taught at Brock, so it's wonderful to have the opportunity, I think, to use what you're discovering and share it in that way. It's fantastic.

[0:34:45] KM: We couldn't do this without our community support. The community supports us in so many different ways, from supporting infrastructure for the project to, again, their support of actually doing the work, either historical or archaeological. We will be actually mounting an exhibit at the Brock University Library, beginning September 1st, which will show the efforts, again, of this co-produced project of volunteers and the academic team, or my research assistant, all pulling together to take what we've learned from the site and to showcase it for the public, and for the Brock community who have been also so incredibly helpful in helping to support the archaeological work, but also being very generous with their time and supporting reporting of far work.

Louis Shickluna was about his people. He looked after his people. He looked after his workers and his family. I feel that's my responsibility now to take that forward to, again, mark his legacy, using the community, using those that are part of St. Catharines in the present, and again, mobilizing them to tell the story of this wonderful shipbuilder.

[0:35:59] AH: As you said, he participated in the community, he participated in local government, and so on. He was involved in so many areas. A remarkable man. We encourage everyone to get out to Brock and see that exhibit, if you can. It's opening soon. We'll put a little bit of information about it on the page for this episode, so take a look at that. It reminds me, though, something you and I have talked about, which is that information on this topic is not so easy to find. It's easy to find when you have Kimberly in the room with you, like I do, but we don't all have that luxury, so is there anything you can recommend to people? People want to learn more about this and explore this area a little bit, resources for them to follow up?

[0:36:37] KM: While there are a few secondary sources about shipbuilding in Niagara, and certainly, of course, with regard to the industry as a result of the Welland Canals, there isn't certainly one source, one specific source to go to in order to learn about that. I am, in fact, working on that. As you might imagine, there are a wealth of certainly, primary sources if you pay attention if you do the work in order to source that material, but it takes time. I've been working on this now for many, many years to try and pull together an accurate history that not only speaks to the shipbuilders, speaks to, of course, the canal developments, but speaks to Niagara's marine sector.

In fact, some of this work is being done in conjunction with my work with the Niagara Community Observatory. Part of the Wilson Foundation Project is about telling Niagara's economic history, and economic development, and through the Wilson Project, we will be doing so across five different sectors. For me, I am, of course, writing the marine sector and, of course, those developments from the earliest period right through until 1969 when our colleagues will take over and continue what happened after 1969. Again, trying to shape the bigger picture of how these industries developed and all of the different interconnections between the different sectors that helped to shape Niagara and shape it into what it is today.

[0:38:14] AH: Which we're all fortunate for in beneficiaries of living in such a wonderful part of the country and a part of the world. Definitely, I think, I'm certainly looking forward to seeing how that comes out. I hope, too, with the upcoming bicentennial of the opening of the Welland Canal, there's going to be a lot more attention and focus on, I hope, resources and funding available to you and to people who are doing the work you do. Because this is an area that we don't know enough about. I think, as everyone can see, it's a really interesting topic, but also complicated. For all the work you've done, I think you've referenced it a couple of times that there's so much more to do.

[0:38:49] KM: There is. Unfortunately, there are not enough marine historians doing the work. We're a very small sector of historical inquiry. Yet, when we think about our histories, if we are neglecting our marine histories, we are certainly doing a huge disservice to understanding this province that is made of 200,000 lakes and countless number of rivers and tributaries. We are made on the water. By reconnecting with these marine histories, of those that helped to shape, of course, the region will be important to understanding us, to understanding how we are, how we've arrived, where we have today.

[0:39:33] AH: Definitely, everybody, check out the resources we've got listed on our page for this episode. Get out to Brock and see that exhibit and look for the next stage of the Shickluna Shipyard Project and look for your chance to get involved, because it's a really unique opportunity, which, as you're saying, does not come around often to get involved with a project of the significance that's part of our history and heritage. Thank you so much, Kimberly, for making that available to people. Thanks very much for making yourself available to us today. It's been great to learn more about this. I've always enjoyed it. We had so much more we can talk about as well. Let's not say goodbye. Let's say, until next time, we'll do this again soon.

[0:40:11] KM: That sounds good, Andrew. Thank you so much. It's wonderful to speak about this topic.

[END OF INTERVIEW]

[0:40:18] ANNOUNCER: Thanks for listening. Subscribe today so you won't miss our next episode. To learn more, or to share your thoughts and show ideas, visit us at thebrownhomestead.ca on social media. Or if you still like to do things the old-fashioned way, you can even email us at opendoor@thebrownhomestead.ca.

[END]